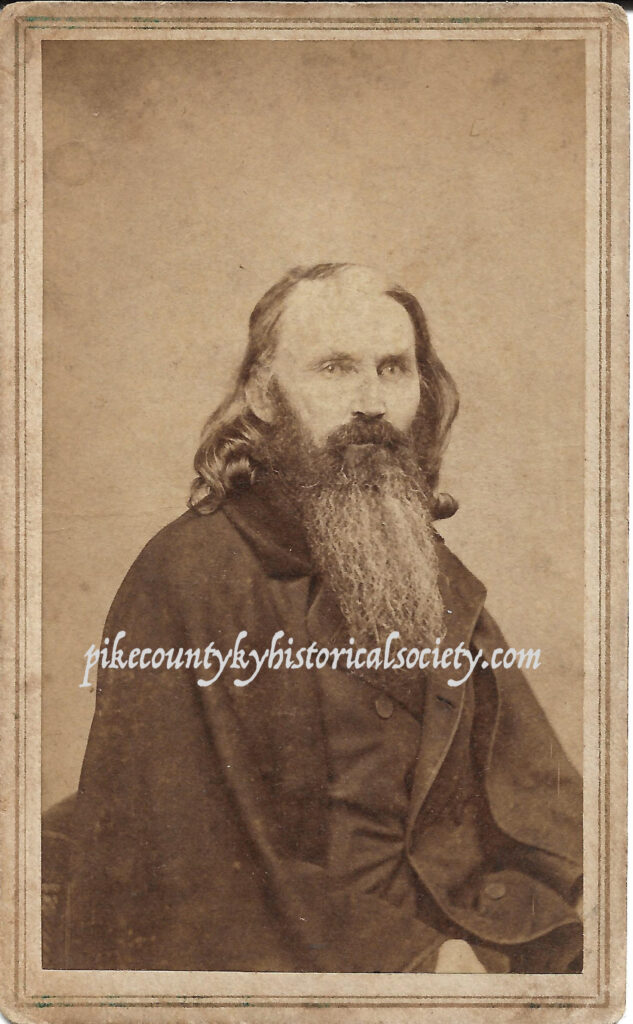

Beginning on the next page is an autobiography of JOHN DILS, JR. which was published in William Ely’s 1883 “The Big Sandy Valley”. Photos are from my collection, not from Ely’s book.

In the autobiography Dils concentrated on his family history, his early days in Pikeville, his marriage, his business associations, and his motivation for becoming involved in the Civil War.

I have intermittently researched Dils’ story over the years and have accumulated several documents. I was fortunate to get a copy of the only known photograph of Dils from life, furnished by Rick Johnson from the Imogene Daniels Johnson collection.The Frankfort studio which produced the photo operated only from August 1864 to August 1866. The fact that he is wearing a greatcoat makes it likely that it was taken during cold weather.

In getting up the material for the history of the people of the Big Sandy Valley, the author invited Mr. Dils to furnish for its pages all of the more important events coming under his notice. During his nearly half-century residence in the Upper Sandy country, constantly mixing with the people in their social, business and political affairs well qualified him for furnishing historical matter impossible to get from any other source.

The graphic and scholarly way in which he has discharged the task is sufficient reason for giving his manuscript, as it came from his own hands, a place in the book, without any alteration whatever.

Colonel John Dils was born, 1819, in Parkersburg, Wood County, now West Virginia. His father was John Dils, Sen., and his grandfather bore the same name, who, together with his brother Henry, emigrated from Pennsylvania, on the Monongahela River, near Brownsville, and came to West Virginia, and settled in Wood County, near Parkersburg, about the year 1789. They had both served in the War of 1776, and were active participants, with the Ohio colonies of Belpre and Marietta, in the Indian troubles on the frontier, in the early settlements of that day. His father was with the Wood County militia under Colonel Phelps, who went to arrest Colonel Burr and his men on Blennerhassett Island, under the proclamation of President Jefferson in 1806. But failing to find him on the island, Colonel Phelps, with a part of his men, hastened to the mouth of the Big Kanawha River to intercept Colonel Burr’s retreat; but Colonel Phelps was again foiled by the wily foe.I Have often heard my father express words of sympathy and kindness toward the unfortunate Blennerhassett and his beautiful and accomplished wife, who were the owners of the historic island that bears their name. To be reared amongst the living actors of those stirring events of our country’s history, has made an impression and left a charm that no romance or fiction has ever been enabled to supplant the real, as inbibed in my early boyhood. The very air was rife with the tales of the wonderful deeds of early frontiersmen. Ransom, a swarthy, dwarfish negro, who became the property of my cousin, James Stephenson, was the servant and waiter of his royal queen, Mrs. Blennerhassett. He was a good idler, and a favorite with the youngsters in his nocturnal visits, and many were the joyful reels I participated in under his teaching and inimitable music; and when tired with “tripping the toe,” we would gather around our sable friend to listen to some wonderful stories he was so fond of relating of the prairie queen whom he had so proudly served, but now “far away from her own dear island of sorrow.”

But it was meet for me the spell should be broken, by leaving dream-land and the magic of the hour. In 1836 Mr. Callihan, who had married by sister the year previous, stopped at Parkersubrg on his return from an Eastern trip of purchasing goods, to get me to accompany him to his home at Pikeville, Ky., which I accepted, as I was anxious to be with my sister.

And thus it was Big Sandy became my future home, where I now live, and I have resided ever since, save a short time during the late war, when it became expedient to remove my family to a safer and more congenial place. The impression, as I traveled along up the Big Sandy Valley for the first time, would be difficult to recall, save its wild but rich presentation of both land and forest, and its far excelling any thing that I had ever seen. The people I found to be plain and simple, with unbounded hospitality. Most of them were the early pioneers of the country; some had been soldiers of the Revolution, and many others of the War of 1812 and the Indian wars. The country abounded with game. Bear and deer were abundant, and hunters were numerous and happy. Hunting was the principal occupation of both young and old. In the season for killing game a man without a gun was out of occupation, unless he was a merchant or preacher. A good gun was worth a good farm or first-class horse, as I have often heard hunters say.

The peltry taken from the wild animals found a ready sale. Many a fat bear and deer’s carcass, after being stripped of its hide, was left to be devoured by ravenous wolves, wild-cats, etc. It would be marvelous to the present generation should I relate some of the old hunters’ yarns of experiences in their hunting and expeditions. I am now thinking of some of the old Nimrods; such men as the Pinsons, Maynards, Colleys, Belchers, Owens, and a host of others, not forgetting Uncle Barney Johnson of block-house and golden wedge fame. This golden wedge Barney plowed up on his farm from an Indian burying-ground, and gave it to a blacksmith neighbor to braze bells with, not knowing its worth. I heard the brazier say it was the best brazing metal he ever had in his shop.

In addition to the abundance of game to supply the roaming hunter, it was the land of honey and ginseng. It was no trouble for a little boy or girl to make from one to three dollars a day in digging the latter article. It was generally collected in the Fall of the year in its green state, and sold to the merchants, who had I clarified for the Eastern market before shipping. Ginseng was the principal commodity of exchange in all the Upper Sandy counties, and I can only say the amount collected was really fabulous. But the bear, deer, and ginseng have long since mainly disappeared, and the fine timber of the forests is fast following in the same footsteps.About the 1st of December, 1837, I was intrusted by Mr. Callihan with a considerable amount of money, which I belted around me, to overtake a large drove of hogs which belonged to Mr. Callihan’s partner, H. B. Mayo, of Prestonsburg, and which was in the care of his son, A. I. Mayo.

The country I had to pass through was entirely strange to me, with only a settlement here and there, being almost an entire wilderness. As I had to pass through the Pound Gap of the Cumberland, but little better than a bridle-path, and as I had heard that was the main passage of the Goings and Murry gangs of horse-thieves, to East Tennessee, I had many misgivings whether I would be able safely to deliver the money. But, nothing daunted, having procured a weapon, I had determined to deliver the charge or die in the effort.

About twenty miles from Pikeville, where the Shelby Creek forks, instead of going to the left, I took the right-hand path, and after traveling near fifteen miles from the direct road to the Pound Gap, I learned my mistake, but was told if I would cross the mountain, which was very high and rough, to the left, I could again fall into the right road, some six or eight miles distant. It was then snowing heavily. I was directed to follow a dog-trail which had just passed over the mountain, returning home from a bear-chase; but while I could climb the rugged mountain with little difficulty myself, I found it quite different with the horse I was leading. Indeed, I found the progress so slow and the dog-trail becoming so dim and difficult to follow from the snow-storm, with also a good prospect of a night’s lodging in the snow, my better judgment was to right about face and retrace steps, which I hastened to do, as night would soon be on me. I was near ten o’clock when I drew up at the house of my kind friend, S. Hall, that night, for the lodging, having traveled fifteen miles, with no other incident than having the pleasure of seeing a large bear cross my path and not more than a mile from Mr. Hall’s house. After partaking of a hearty supper of good fat bear-meat, sweet milk, corn-bread, etc., and relating the incidents of the day, not forgetting to mention I desired an early start in the morning, I soon found myself tucked away in good, warm feathers, with a light heart, happy in the thought that the belt with the money was all safe around me, and by the next day’s travel, nothing happening, I would be relieved of all dread and care by safely delivering it over to Mr. Mayo; all of which it was my good fortune to accomplish after traveling more than fifty miles, not seeing over half-dozen houses in the space.[1]

[1] Dils’ circuitous path would have taken him along the State Road which was opened in 1837 By Thomas May. He would have gone up onto Indian Creek and again pick up the State Road at its mouth, but, instead, he backtracked and crossed the Indian Creek/Robinson Creek gap onto Road Fork of Indian Creek. Two miles farther and he would have reached the home of Samuel Hall, a justice of the peace, near the point of the present Valley IGA supermarket, where the State Road met Long Fork.Levisa Fork to the mouth of Island Creek; up that stream and left up Road Fork; then up the mountain; through the gap onto Sookeys Creek; then onto Robinson Creek where he made his mistake by turning right. He would have gone up Robinson Creek, probably to the Ray family home, where he learned of his error. He was told that he could cross the mountain to the mouth of Island Creek; up that stream and left up Road Fork; then up the mountain; through the gap onto Sookeys Creek; then onto Robinson Creek where he made his mistake by turning right. He would have gone up Robinson Creek, probably to the Ray family home, where he learned of his error. He was told that he could cross the mountain.

In 1840 and 1841 I taught two subscription schools of five months each per session. In November, 1842, I was married to my present wife, Miss Ann Ratliff, third daughter of General Wm. Ratliff, of Pike County, Kentucky. The following year I went into the mercantile business with R. D. Callihan and Jno. N. Richardson, known as the firm of Jno. Dils, Jr., & Co. In two years following, it was changed to Richardson & Dils.

In 1846 the war with Mexico broke out. President Polk issued a proclamation, calling for volunteers, and a company of one hundred men was made up at a general muster, a few days after the announcement. I was elected captain, C. Cecil, Sen., first lieutenant, and Lewis Sowards second lieutenant; but the company was never called into service on account of being too remote for transportation.

In 1852, after twelve years of uninterrupted pleasant business relations with my friend and partner, J. N. Richardson, I bought him out, and continued the business in my own name until the War of the Rebellion in 1861. In October of the same year I was arrested at my own house, by the order of Colonel Jno. S. Williams, who commanded the Confederate forces, then camped around Pikeville.

JNO. S. WILLIAMS, C.S.A.

I was only a private citizen, but was treated as a felon, and sent as a prisoner of war to Richmond, Virginia, under a heavy guard, and placed in the notorious Libby Prison for safe-keeping.[2] My wife came to Richmond as soon as she could get permission to pass through the lines, and I was liberated a few days before Christmas. As we were traveling through Buchanan County, Virginia, on the head of Sandy River, we stopped to feed our horses and take supper, in order to reach Grundy[3] that night, so as to make the next day’s ride lighter; for we were anxious to get home the day following, to see our little children, whom she had left in the care of a trusty servant and a brother-in-law.[4]

[2] In “Richmond Prisons 1861-62” by Wm. H. Jeffrey, 1893, Dils, along with William Ferguson and Clinton Van Bushkirk [sic], the two who were sent to Libby with him, are listed as prisoners on pages 229-230.

[3] They returned by the same route Dils had been taken to Richmond: up Levisa Fork; past Card Ridge into Virginia; then to Wytheville, where they would have taken the Virginia- Tennessee Railroad and made connections to Richmond.

[4] That brother-in-law was Joseph, Harrison, or Lane Ratliff, all Ann’s brothers.

But that night’s ride came near being my last. About a mile from where we got supper, we were called to halt by a party concealed in the timber on the hill-side. My wife was just before me on a bridge. As she did not hear the summons, I called out to her to stop. I asked the concealed party what they wanted. They evaded my question. I requested them to come down; I wanted to see who the were, so I could report them. They halloed out, “Go on.” We started, but I was fired at three times before I got that many lengths of my horse, the shot just brushing the back of my head, and dashing the little twigs from the brush in my face. We moved up pretty lively after that for a few miles.

I visited Washington the February following, with a view of getting relieved from any military obligation I might be considered bound to observe to the Confederate States. I was neither sworn, nor did I sign any parole, but was simply discharged, as I understood. But still I did not feel just like a free man; not that I wanted to go into the service, but I knew my failing: I would speak out my sentiments—therefore I desired to be relieved from any trammels, however constructively viewed. After seeing my friend, Hon. Green Adams, I laid the matter before him to assist me in the difficulty.[5] My friend introduced me to the President, Abraham Lincoln, who gave me a special invitation to visit him as often as I could, which marked favor I was pleased to accept, seldom missing a day, as each visit made it more interesting and charming as time faded away. I refer to this, as it was my good pleasure to have the opportunity to listen to what the good man had to say to each of the many who were hourly petitioning him for some favor, and wherein his inestimable worth could be seen both in the Executive and the great, swelling, loving heart for the people.In August 1862, some of the advance troops of General Kirby Smith arrived near Pikeville. I was robbed of a large stock of goods by a party under the command of Colonel Menifee [sic], and some of Colonel Caudill’s command.[6] I had to flee the country for life. I arrived at Frankfort, after stopping a short time in Louisville, the fourth day after leaving home, giving the news of what was going on. I wanted guns, as no peace could be had at home on any terms.

[5] During the Civil War, it was customary to parole enemies if they promised to not take up arms against their captors. By this statement, Dils was probably considering the possibility of becoming involved in the war. If a paroled prisoner rejoined the army and was captured a second time, their broken oath could be punishable by death. Dils wanted to avoid this possibility.

Green Adams was most advantageous to Dils’ cause. Born in Barbourville, he was a lawyer and slave owner. He was elected as a state representative in 1939 and in 1844 was a presidential elector. He became a U.S. representative in 1847. In 1851 he became a circuit court judge for Kentucky and was elected to Congress in 1859. At the time of Dils’ visit to Washington, D.C. in early 1862, President Lincoln had recently appointed Adams as sixth auditor of the United States Treasury. Both he and Dils were long-time members of the old Whig party, which began to crumble with the death of Henry Clay. (Adams biography from Wikipedia.com)

[6] There were two companies of the Fifth Kentucky Infantry, C.S.A. They had marched out of Tazewell County, Virginia, and were under the command of General Humphrey Marshall. One company was commanded by Captain Benjamin Caudill of Letcher County, the other by Captain Anderson Moore of Elkhorn Creek, Pike County. Menefee’s company was not under Marshall’s command, but was part of the Virginia State Line militia commanded by General John B. Floyd. Menefee and his men were primarily responsible for looting John Dils’ store during the night of August 2. Before reaching Pikeville, members of Moore’s Menefee’s commands were allegedly involved in the killing of Peyton Justice. See WHEN SNAKES ARE BLIND on this website.

GENERAL JOHN B. FLOYD, C.S.A.

There were a great many people gathering in Frankfort, as the State was in a fever of excitement. Governor Magoffin resigned, and the Hon. James Robinson was inaugurated. I had the pleasure of seeing Senator J. J. Crittenden, with an introduction. He informed me that in the War of 1812 he formed the acquaintance of my father, both being soldiers under General Harrison. I was invited to his house to take tea with himself and his excellent wife, and was very kindly and cordially received. He had much to say to me about the war, and asked many questions about what I had seen while in Richmond, and also about friends who had left Kentucky, and were supposed to be in Richmond. He went with me to the arsenal the next day, to see that I got as much guns as I desired, speaking many kind words in favor of myself and the people for whom I wanted the guns. I found him the “noblest Roman of them all,” and shall ever venerate him for his kindness to me and for the interest he manifested in the mountain people.

Menefee’s company was not under Marshall’s command, but was part of the Virginia State Line militia commanded by General John B. Floyd. Menefee and his men were primarily responsible for looting John Dils’ store during the night of August 2. Before reaching Pikeville, members of Moore’s Menefee’s commands were allegedly involved in the killing of Peyton Justice. See WHEN SNAKES ARE BLIND on this website.

A commission to recruit a regiment came to me at Catlettsburg about the first of September, without any solicitation or agency on my part; I learned that it was done through such friends as the Hon. J. J. Crittenden, Garrett Davis, and others.[7]

It was several days before I could get my own consent to accept; but, there being so many refugees from the Upper Sandy counties (Pike, Floyd, etc.) that wanted to go into the service of the United States army soliciting me, I finally acquiesced and recruited the first day about two hundred men, and soon after raised, at a considerable personal sacrifice, what is known as the 39th Kentucky Regiment, Mounted Infantry. Its efficiency or inefficiency as an auxiliary in the service of the Government has gone into history, to stand the test of an impartial judgment of the loyal mind, where its friends rest in confidence of a just verdict.

J. J. CRITTENDEN

GREEN ADAMS

GARRETT DAVIS

(Wikipedia.com)

[7] Dils and Garrett probably knew each other by reputation. Davis led a contingent of volunteer cavalry as part of General William “Bull” Nelson’s army during the early fall 1861 fighting at West Liberty, Ivy Mountain, and Johns Creek. Nelson’s army occupied Pikeville only days after Dils’ arrest and had surely heard of the event. Dils, on the other hand, likely knew Davis’ statewide political reputation and no doubt heard of Davis being in Pikeville during his confinement in Libby Prison.

END OF AUTOBIOGRAPHY FROM ELY

Dils’ reputation was built primarily upon his Civil War service. Although a slaveholder, he was a staunch Union man. He was opposed to the Southern Democrats who controlled the town and most of Pike County, and had been a Whig until dissolution of that party. For a brief period, while thrashing about without a political anchor, Dils voted the American or Know Nothing party ticket. At the beginning of the war, he found himself in a precarious social situation due to an affair with an unmarried woman.

Sarah Caroline Edmonds was born in Smyth County, Virginia. She was commonly known as Caroline. At some point after 1850, she came to Pike County. In the 1860 census, at age 21, she was living across the river from town in the home of R. P. Robinson. At some point during the late 1850s, she and Dils became embroiled in an affair. Whether that was the reason she was living with the Robinsons is not known, but it came to the point that Caroline’s father, Preston Edmonds, filed a civil suit against Dils. In what was essentially an alienation of affection case, Edmonds complained that Dils had robbed him of the affection, attention, and services of his daughter. The outcome of that matter is not recorded.

SARAH CAROLINE EDMONDS

(Courtesy of Stan Edmunds)

When Dils was sent to prison, Caroline turned elsewhere and married a member of the 14th Kentucky Infantry, U.S., from Louisa. She moved downriver to be with her husband, but the marriage was short lived. When the 14th was sent south to serve in the Georgia campaign, Caroline’s husband was killed in action. Left a widow, it seemed that her affair with Dils was history, but it would soon become evident that the flame had not died.

The seeds of Dils’ destruction as an officer in the Union army were sown practically as soon as he was commissioned. The 39th Kentucky was organized during the fall of 1862, whereupon Dils moved his force upriver to Pikeville. Contrary to what he wrote in his memoir, Dils did not get all the guns he wanted in Frankfort. During November 1862, a shipment of shoes, socks, and winter uniforms, along with 300 Belgian rifles and several thousand rounds of ammunition, was loaded onto 10 flatboats and sent upstream for the 39th Kentucky. The summer and fall had been unusually short of rainfall and in August a person could have walked across the stones on the river bed at Louisa and never got their feet wet. Once they reached the swift current at Wireman Shoals on the Johnson-Floyd county line, the boatmen unloaded and portaged the cargo on land past the shoals and reloaded the boats on the upriver end. They settled in for a night’s rest.

General John B. Floyd at the time was making a sweep with his Virginia State Line cavalry down the West Virginia side and back up the Kentucky side of the river. Floyd’s cavalry commander, Colonel John Clarkson, reported the boats coming up Levisa Fork. Floyd then dispatched several hundred mounted men through the mountain gap onto Brushy Creek, then down to Prestonsburg. The Confederate riders attacked the boats’ guard at daybreak and spent the day unloading the cargo, packing their mounts, and finally burning what they could not carry.

Later that evening, near midnight, the booty-laden Rebels met two companies of the 39th Kentucky under Colonel Dils in the crest of the gap of Morgans Mountain, known today as Bull Gap. Snow was heavy and so was the aimless exchange of gunfire. One Rebel, later identified, probably erroneously, as Samuel Bird, was killed and later buried where his body was found. Colonel Dils was riding a spirited horse, which spooked amidst the clamor. It would have been better had he been thrown clear, but his foot caught in a stirrup and he was dragged a distance down the mountainside. He would be plagued with drainage and near deafness in that ear for the rest of his life.

HEADSTONE OF SAMUEL BIRD (?), KILLED 12/4/1863 IN THE GAP OF MORGANS MOUNTAIN

The State Line force continued on to Pikeville, then took up a march toward Tug River to join up with the main contingent under General Floyd. During that maneuver, several known Union men were arrested. One of those was Asa Harmon McCoy, who had been wounded in Pike County the previous February while in Union service. He was taken to Richmond, soon released, and ended up in Bethesda Hospital where a Union surgeon issued a report describing his wound and its complications.[8]

[8] McCoy was the brother of later feud leader Randolph McCoy. He recovered sufficiently to be released from medical care, then returned home and promptly rejoined the Union army. He was killed during the winter of 1864-65, allegedly by Devil Anse Hatfield and Jim Vance.

Dils and the men of the 39th shivered through the winter without woolen uniforms, generally living with family or friends. Once spring arrived, Dils established a headquarters camp and consolidated his scattered regiment. He named the post Camp Finnell, in honor of the Kentucky Adjutant General who had restocked the 39th’s clothing and armaments. One of the regular, familiar sights in camp was that of Caroline Rowe, Dils’ old flame. Outfitted with new rifles and fresh uniforms, the spring and summer of 1863 would mark the wartime highlights for Dils’ and his men.

On April 15, after a forced march from Louisa, Colonel Dils and his troops captured a contingent of some 77 Rebels camped on Pikeville’s public square. The Rebels were commanded by Major James Milton French, a pre-war Wise County lawyer who had also practiced in Pike. Dils was later credited with stating that French was the only honest Rebel he had known. That said little for his brothers-in-law, Joseph, Lane, and Harrison Ratliff, his nephew by marriage, W.O.B. Ratliff, and his father-in-law, William General Ratliff. The prisoners were part of what would have become the 65th Virginia Infantry, C.S.A. Instead, they were sent to Louisville, then to Camp Chase, Ohio, and finally to Baltimore and a prisoner of war exchange at City Point, Virginia. The most recognizable figure in the group was Martin van Buren Bates, a giant of a man from Letcher County who had served out his enlistment with the Virginia State Line in March. Most notorious among the returning prisoners was Clarence Prentice, son of George Prentice, a Louisville newspaper editor and friend of President Lincoln. Bates would soon become part of Prentice’s 7th Confederate Cavalry Battalion, C.S.A, an outfit which would make its own reputation for thievery and general outlawry in eastern Kentucky and southwest Virginia.

Dils’ second victory came in early July 1863. The 39th Kentucky and the 65thIllinois Infantry under Colonel Daniel Cameron were involved in a sweep up the Tug River valley. Along they way they arrested known Confederate sympathizers, burned barns, and confiscated livestock. On July 5 they engaged a group of new volunteers in the 45th Virginia Infantry Battalion, C.S.A. The 45th was being organized largely from Colonel Henry Beckley’s old regiment, the 1st Virginia State Line. One of those captured in the fight at the mouth of Pond Creek was Randolph McCoy, brother of Unionist Asa Harmon McCoy and soon-to-be leader of one faction in the infamous Hatfield-McCoy feud.Despite his victories, complaints against Colonel Dils mounted as the temperatures grew hotter. Charges included: neglect of duty; conduct unbecoming an officer by keeping a lewd woman in camp; confiscating some 900 horses, selling them, and receiving the money therefrom without proof of disbursement to the government; using government boats to transport personal goods; and incompetency. Dils would respond by simply stating that he was disliked because of jealousy and his aggressiveness toward the enemy. Nevertheless, government records showed that 21 of his officers had requested him to resign. Of all the charges, the only justifiable one was that of keeping a lewd woman in camp. The horses confiscated in enemy territory were either used by Dils’ and his men or sold in order to supply the 39th. The boats lost at Wireman Shoals indeed had carried private goods, but were private property, not owned by the government.[9] Neglect of duty charges were rampant among Union officers and it was practically unknown that one was dismissed on that charge alone. Incompetency could not be supported; Dils had impressive victories to his credit. In fact, General Burnside, the department commander who approved Dils’ dismissal had himself been transferred Department of Ohio due to his poor performances at Fredericksburg and other battles. It would be of no satisfaction to Dils, but some of his detractors in the 39th later testified that, had they known their grievances would lead to their colonel’s dismissal, they would have kept silent.

GENERAL AMBROSE BURNSIDE

(Wikipedia.com)

[9] An aide to Colonel John Clarkson, who was the Virginia State Line cavalry commander at Wireman Shoals, later wrote to his father in Virginia that he had taken a fine pair of lady’s shoes off one of the boats. They had been intended for his mother, but were stolen before he could send them home.

The allegation of keeping an unmarried woman in camp seems to have been the underlying motivation for Dils’ dismissal from service. General Jeremiah Boyle, a superior officer evidently sympathetic with Dils’ case, wrote of the colonel’s indiscretions, “. . .he should have known by this time that the conduct of a gentleman was demanded of him.” By November 1863, it looked like he would weather the storm. On November 3, after being temporarily relieved of command, General Boyle ordered him reinstated.

During the following five weeks, however, the Union command hierarchy did an about-face and made an end run around General Boyle. On December 10, the friendship with President Lincoln that Dils would later mention in his autobiography proved to have been short lived. On that date he was dismissed from service by direction of the President, upon the recommendation of General Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Department of the Ohio.

John Dils, Jr. was once again a private citizen.

Dils did not give up easily. He contested his dismissal and petitioned for reinstatement several times. His wife continued the efforts after his death. All appeals were denied.

Included in this section is an 80-page transcription of Colonel Dils’ court martial file. It was gifted to me years ago by Nancy Forsythe of Pikeville. All markings and notations are by previous owners.

Also included is a transcription of a lawsuit styled “Dils versus May.” Immediately after the Civil War, Dils went to Boyd County and filed a lawsuit against Henry May. In it he alleged that May had acted as guide for Nathaniel Menefee and led him to Pikeville on August 2, 1862, in order to loot Dils’ store. Dils was probably hoping to have his case heard by a favorable Union audience, but the suit was moved to Pike County, home of both parties. The suit continued on, with occasional testimony being taken, until it was finally settled in May’s favor by the Kentucky Court of Appeals in 1882. It was one of the longest running Civil War related lawsuits in Kentucky.

Senior Historian Authority / Civil War – Randall Osborne

John Dils Court Martial

Interesting read of John dils. My family was in his unit of the 39th me Tu ku mounted.