A Young Man Hanged and a Family Avenged

Barbara Vance Cherep

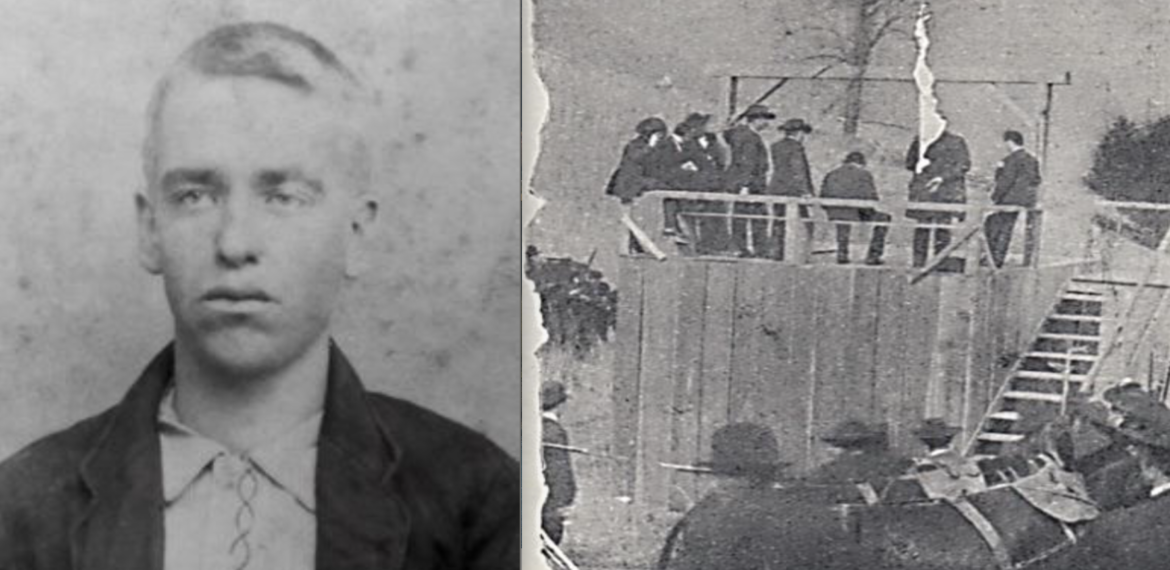

“Ellison Hatfield-Mounts, a Hatfield confederate who had admitted to the shooting of Alifair McCoy, and was then hung by the neck until dead.” Those were the newspaper headlines so numerously printed across the country, when the small mountain town of Pikeville Kentucky became the backdrop for poetic justice. Ellison, this simple rustic paid the ultimate Penalty of Death for his sins, and the sins and squabbles of these two families; the Hatfield’s and McCoy’s. Ellison had admitted to murder. Pikeville, the McCoy’s, and the state of Kentucky had avenged the murder of Alifair McCoy for the New Years raid on the McCoy cabin.

Imagine the scene of this justifiable death sentence per a Pikeville jury. Ellison is standing on the scaffold, looking to the majestic hills of West Virginia for any last attempt at a rescue by his family and friends. Yet no one came. Rev. Glover asking young Ellison for any last words. Ellison, who was about to meet his maker could only say “he had no speech to make, but that he was prepared to die, and wanted his friends to be good men and women, and meet him in heaven”. Ellison then kneeled down to the glory of God asking for everlasting life. It was then that this young man spoke his last amen. He stood solemn and tall as the hood was pulled over his head by the deputy sheriff. The noose being tightly drawn around his neck. The door opens and Ellison dropped to his death on February 18, 1890. Kentucky had made its point! The feud, all feuds must come to an end. [1]

Per Randal and son James McCoy, in court, said the feud began in 1882, with the murder of Ellison Hatfield, brother to Devil Anse Hatfield. Not during the civil war. Ellison was murdered 1882 at a political gathering. Three sons of Randal McCoy committed this murder; Farmer, Tolbert, and Randal Jr. The elder Ellison Hatfield, a bother to Anse Hatfield, is stabbed 26 times and shot by these young men. A horrific murder of a family man with a wife and young children. Anse Hatfield avenging his brothers death took possession of the three McCoy’s and made them pay a heavy price by shooting them execution style. This led to five years of Pikeville court entries, ongoing from term of court – to term of court. But alas, the Hatfield’s must be brought to justice. Gov. Buckner at the bequest of Perry Cline put a reward on their heads. R.M. Ferrell in Nov. 1887, then Pike County Clerk, giving Gov. Buckner warning of more violence if these rewards were not dropped. Buckner would not withdraw the bounties. A desperate act, this led the Hatfield’s to the New Years raid on the McCoy home, where Alifair was killed.

Visualize it is 1887, New Year’s Eve, nine o’clock at night. A blustery cold evening with the moon fully visible to the naked eye having lit up the night sky. Randal McCoy and his family had just gone to bed. The home being made of logs consisting of two small buildings, one which held the kitchen and beds of Randal and wife Sarah. Up above was a loft where Calvin and little Melvin, son of Tolbert would sleep. The second structure was attached only by a roof and separated by a dog trot where the McCoy daughters slept.

(Library of Congress photo)

The family had gone to bed when Randal and Calvin were awakened by the hounds barking. Soon 25-year-old Calvin was by his father’s bedside, “They are coming on us, Pa”. The house was surrounded and a voice shouted from the woods, “g__ d___ you… come out and surrender yourself a prisoner of war”. Randal did not oblige the command from the woods. Then several volleys of bullets came through the door. Randal and Calvin went up into the loft for a better vantage point to return volleys of bullets themselves, but to no avail. Randal would not succumb to the men in the woods. It was then that the unseen enemies sent the McCoy home up in flames. The gunfire kept at a steady pace from both sides. Randal and Calvin then joined Sarah and Melvin in the kitchen, steps away from the door. Randal could hear exchanges of words between Alifair, then 29 years old, speaking with someone from the woods she called Cap. Cap Hatfield was the son of Anse Hatfield. Per testimony of Randal, Alifair was said to have replied to Cap Hatfield and Hense Chambers with, “You wouldn’t shoot a poor innocent woman, would you?” More words rang out, “Shoot her, g__ d___ it. Shoot her down, spare neither man nor woman”. It was then that Cap Hatfield took aim at Alifair, but it was Ellison Hatfield-Mounts who took the shot, shooting her in the breast. Randal heard her fall to the ground near the door. Sarah McCoy, her mother, went out the door where she was beaten over the head and back with a rifle by Johnse Hatfield.

Forging a plan, Calvin and Randal decided to make their escape. Calvin told his father he would go out first and run toward the barn. Calvin would draw the attention of the men in the woods. Sacrificing himself, Calvin went out the door, leaped from the porch, and started running. He was shot through the head while running to the barn. Six-year-old Melvin was clinging to his grandfather’s leg when the elder McCoy decided to run for safety. Randal pushed Melvin away and back into the room of the burning house, but not before seeing Johnse Hatfield on his way out the door. Johnse, with his gun having caught foul, was down on one knee working to unjam his rifle. Randal took aim at Johnse hoping to kill him, but, using squirrel shot, he fired too low, striking Johnse in the shoulder instead of the head.

Randal took cover in the shuck pen before making his way to the home of Johnse Scott, staying there until the next morning. Leaving his family dying and in the cold. This likely preyed upon the mind of Randal McCoy for years.

Early morning New Year’s Day, James McCoy, eldest son of Randal, arrived on the horrific scene with neighbor Johnse Scott. What they found at first daylight was a ghastly sight of Calvin lying dead on the frozen ground with a bullet to his forehead. The house was nothing more than smoldering logs. They walked about 30 yards up a ravine, where lay a mattress which had been pulled from the burning home by young Melvin. Alifair was dead, her blood-soaked hair frozen to her breast. Positioned between Sarah and Alifair were the two children of Tolbert McCoy, Melvin and Cora. Melvin, like Randal, in 1899 testified to what he remembered. Melvin slightly varied from the testimony of Randal, but not so much that it changes the overall scenario. [2]

The different modes of communication (i.e., letters, telegraph, newspapers, spoken words) made for the many discrepancies on the feud lore, which is why the “conversed and printed feud” is still ongoing today. Here we used the testimony of Randal and James McCoy from the 1899 Johnson Hatfield trial for the murder of Alifair. As with any sworn testimony, there was likely more than a trickle of truth in their testimonies.

Ellison Mounts was found guilty of the murder of Alifair by the Kentucky Appeals Court in Frankfort in 1889. His agreement with city officials (i.e., P.A. Cline, Sam. M. King, D.W. Cunningham, T.M. Gibson, J.M. York, Col. John A. Dils, and John Lee Ferguson) had been broken in an earlier criminal trial in Pikeville, if indeed it was a true confession he made. The deal was that, if Ellison swore to the murder of Alifair, in exchange he would spend life in prison and not be hanged. That was the supposed deal. The Superior Court in Frankfort upheld the sentence of death handed down by the Pikeville jury. Sheriff Maynard signed the back of the warrant that the deed was done. Ellison had been hanged.

Interestingly enough, Sheriff Maynard did not sign a death warrant from the state of Kentucky for the February hanging date, but signed on the back of the earlier death warrant from December. The earlier death warrant delivered that the hanging was to happen on December 3, 1889; “It is adjudged that the defendant be taken to the jail in Pike County and there safely kept until the 3rd of day December 1889, on which day between sunrise and sunset he (Ellison) shall be taken from thence by the sheriff of Pike County, who shall hang him by the neck until he is dead”. Sheriff Maynard signed the back and added: “Executed the within by taking from the jail of Pike County the said Ellison Mounts and hanging him by the neck until he was dead Feb. 18, 1890. W.H. Maynard Sheriff of Pike County.”

This document from the Kentucky Archives, The Commonwealth of Kentucky, named by the archives as the “death sentence,” stated that the hanging would occur on February 18, 1890. The document also provides the manner in which the hanging will be carried out, i.e., in an enclosure convenient to the jail, in the presence of not exceeding fifty persons; and the person or persons having custody of the body of the said Ellison Mounts.

In the 1892 case styled Puckett vs. The Commonwealth it goes a bit further and mentions the statutes in which a sheriff is mandated by Kentucky law. By an act approved March 30, 1880, and made part of section 22, Chapter 29, General Statutes, it is provided that the “death penalty shall hereafter be inflicted in some enclosure convenient to the prison, where the defendant is confined, in the presence of not exceeding fifty persons, ten of who may be designated by the court rendering the judgment, and the remainder by the sheriff executing it. No fee shall be charged to any person or persons that are permitted to witness such execution,” meaning people could not be prevented from viewing the act of hanging, nor could they be charged for the viewing.

The Boston Globe of February 20, 1890 describes perfectly the scaffold: “The hanging took place half a mile outside the pretty mountain town, at the base of a low hill. The scaffold was enclosed as required by law, but the enclosure was only 20 feet square and uncovered. The side of the hill formed a natural amphitheater and enabled the spectators to see everything that was going on.” [3]

Ellison’s description was written as six-foot tall (one article said six-two, 180 pounds) with very light hair, about 185 pounds at good health, and dull gray eyes. He had a high narrow forehead, prominent cheek bone, broad vulgar mouth, a nervous twitching chin, all marks of a character bereft of the finer sensibilities. [4]

Most feud books describe Ellison as educationally and/or mentally challenged. Newspaper articles said he could not read or write and was never educated in any school. Other articles tell us that at the age of nine his mother, Harriet Hatfield, married a man by the name of David Mounts, and that Mounts beat him, enough so that he left his home. In the 1870 census, Ellison is six years of age and living with his mother, Harriet. The 1880 census shows him at 16 years of age and still living with his mother, Harriet, with the addition of stepfather, David Mounts.

Ellison Hatfield was married at the age of 19 to Rebecca J Justice on Christmas Day, 1882, in Logan County. An older 36-year counterpart, daughter of Joab Justice and E. Ferrell. Ellison listed his mother as Harriet and listed no father. When living in Pike County, Ellison was required to testify in the 1882 divorce suit of William and Rebecca Jane Ratliff. That testimony came 1885, wherein he stated his age as 19 and occupation that a farmer, living in Pike County. When asked what he knew of Rebecca Jane Ratliff, he said he “had known her to commit adultery three times since she had been the wife of William Ratliff” once near Alum Creek in Logan; once on Grants Branch; and once below the mouth of Alum in this county, meaning Logan, they committed adultery in the summer of 1884. In defense of Rebecca Jane, others contradicted Ellison’s word and testified that she was abused by her husband and that there were no adulterous affairs with others.

In the introduction of Ellison in the Kevin Costner movie (The Hatfields and McCoys), it is far-fetched to believe he was challenged by God and birth to be mentally incapable of right and wrong. Ellison, a green county boy, lacked education (some use the word “retarded,” meaning intellectually lacking) which proved to be his everlasting downfall. Ellison trusted the system, and especially those Pikeville men who made promises of leniency, such as life in prison, but they sent him down a path, helping to beget his course of existence.

The Saint Louis Globe Democrat of January 22, 1890, offered this interesting snippet on young Ellison; “when young Mounts was placed in the Pike County jail, he was a green country boy, had never been to school a day in his life, and was almost too ignorant to give testimony in his own behalf. He had sense enough to know his condition would be improved if he learned how to read and write, and he prevailed upon some of his more fortunate fellow-prisoners to teach him. Not because the goodness of their heart, but because time hung heavy on their hands. The simple rustic devoted himself so industriously to the well-worn primer that Mr. Ford, the jailer, fished out from among the school books of his own childhood days, and in time Mounts had sufficiently mastered its contents to enable him to both read and write. When it was all over and the day for his execution was fixed, the unfortunate man suddenly evinced a desire to hear of religion. Mr. Ford called a minister, and every moment he could spare he spent with the prisoner, and in time the latter learned to read for himself, and understand the scriptural teachings. Rev. Mr. Glover of the Methodist Church visited the jail, prayed with him and received him into the church.” [5]

Pictures of Dr. Rev. John Wilkes Glover, of the Methodist Church of Pikeville, per the Courier Journal, Feb. 20, 1890. The similarities of the two pictures, the man praying with the young Ellison Mounts moments before he was lynched.[6][7]

Some believe the photo of the kneeling preacher is from the hanging of Henry Hall for the murder of his brother, Randolph Hall. Henry Hall had been convicted and sentence to be hung in June of 1893. Hall had an appeal to Gov. Brown and on Aug. 10, 1893 his execution was upheld. Hall died Aug. 11, 1893. The Times (Philadelphia) on February 26, 1893, printed an article showing this sketch of the hanging of Ellison Mounts. Proving it to be a photo of the Mounts hanging, it was printed in no less than three other newspapers for that same date, six months prior to Henry Hall being executed in Pikeville. [8][9]

Some believe the photo of the kneeling preacher is from the hanging of Henry Hall for the murder of his brother, Randolph Hall. Henry Hall had been convicted and sentence to be hung in June of 1893. Hall had an appeal to Gov. Brown and on Aug. 10, 1893 his execution was upheld. Hall died Aug. 11, 1893. The Times (Philadelphia) on February 26, 1893, printed an article showing this sketch of the hanging of Ellison Mounts. Proving it to be a photo of the Mounts hanging, it was printed in no less than three other newspapers for that same date, six months prior to Henry Hall being executed in Pikeville. [8][9]

The Pikeville newspaper was called The Monitor and Mountain Monitor. S.X. Swimme married Kate Weddington in Pikeville and had purchased the newspaper just prior to September 13, 1889. Therefore, since the lead story with this sketch came from Pikeville, in February 1893, it was then disseminated out to other newspapers. The well-known photograph of the Mounts hanging was taken in February 1890, thus the later sketch had been a drawing from that original photo originating in Pikeville. Note that on the above sketch it says at the bottom “From a Photograph”. [10] [11] [12]

Garnet Clay Porter penned a feud article for The Tribune and the Scranton Republican in 1904 and called it “The Great Feud Battle”. In this article Porter was much too creative with both his verbiage and his personal involvement. He claimed to have been there on Christmas night (not New Year’s), when Randal McCoy knocked heavily on the door of the house of Bud McCoy, where Bud, Garnet Porter, and five others were all armed, drinking, cards, and enjoying the holiday, Garnet telling his sympathies lay with his Confederates of the Kentucky side. Randal had come in wearing just a coat, bloodied, claiming his house had been burned. At this point I couldn’t help to feel that Garnet was self-promoting of his career and inflating his self-importance. Not to say all occurrences in this 1904 article did not have at least some merit, as with the same poetries of his soon-to-be-penned 1933 Wide World Magazine story. As a feud researcher and author, I was taken back by his lack of knowledge of the feud… asking myself, “Was Porter really there or was there more to learn about the feud?” BUT… always a but in these stories – how does this explain the Garnet Porter picture of the hanging? The fact is that Porter gives us a second picture of the Ellison Mounts hanging. Garnet a native-born Kentuckian in 1867 from Russellville, was 23 years of age when Ellison was hanged. Impressionable and most likely overly zealous, he was what the senior newsmen called a cub.[13][14]

Tracking Garnet Porter by the newspapers, they show that he left Atkinson Kansas, arriving in Catlettsburg, Kentucky about February 1, 1890. Ellison Mounts was executed on February 18, 1890, not quite three weeks later. Garnet was in Catlettsburg to work with his brother and reporter, Thomas R. Porter. [15] The Atchinson Daily Globe of February 1, 1890 it states; “The late G.C. Porter is now associated with his brother in the publication of a weekly paper at Catlettsburg.”

Below are the excerpts from the 1933 Wide World Magazine wherein the second celluloid photo of the Ellison Hatfield-Mounts hanging was finally put on public display. In his words, his narration of his story. Mr. Porter calls Mounts a Hatfield, as did many other feud era newspapers and even court documents. His mother was a Hatfield who gave birth out of wedlock. He carried her name, by birth and law, being unmarried. [16]

Porter wrote: “I observed that the prisoner shaded his eyes and glanced hurriedly out of a window in the corridor opening toward the east… where lay his hope of succor. Outside the prison was a wagon drawn by two big mules. The condemned man, an old back wood preacher, and two armed officers with rifles across their knees took their places in this vehicle. Other armed men marched alongside, accompanied by a number of newspaper reporters and a small curious crowd. The ride was accomplished in utter silence, but I noticed that Hatfield kept his eyes constantly focused on the mountains. As we approached the scaffold a crowd of perhaps three thousand persons came in sight. The scene of the execution was a beautiful mountain valley, a natural amphitheater perhaps a mile in circumference. Toward the Virginia side a score of riflemen were posted, ready to deal with any attempt at rescue. At the scaffold there was a disturbance; two or three McCoys wanted to get up on the platform, but the sheriff objected. I was standing just behind the prisoner; the sheriff was immediately behind me. Bud McCoy and Frank Phillips, drunk and excited, were determined to ignore the officials order to stand away. Together they pulled the sheriff down, and a quick scuffle took place. The men were soon hustled away, and no guns were used, but the sheriff was badly hurt and unable to climb the steps again.

I had taken my position at one side of the roughly-constructed scaffold. I am the hatless figure to the right of the picture, which shows something white in my breast pocket. This was not a handkerchief, but the envelope which had contained the death-warrant. The document itself was in my left hand at the moment when the photograph was taken. It was the injury to the sheriff that thrust me into prominence, and the full import of what followed did not draw upon me until too late.

“The sheriff being temporarily incapacitated; the warrant was passed up to his deputy. This man could not read… or pretended he couldn’t… and as I stood next to him, he pushed it into my hand with the request that I would perform that part of the ceremony. I took the document and was reading it aloud, almost before I realized what I was doing.

“After the reading of the warrant, the preacher (who is seen standing to my left) said a prayer. Meanwhile the prisoner remained seated, with the death cap partially rolled down over his head. A moment later Hatfield stood up, and as an officer began to adjust the noose, he once more gazed searchingly toward the Virginia mountains. Moments later the execution was over”.

“When we started the return some of my Pikeville friends remarked that the sheriff has served me a shabby trick by putting me forward to read the death warrant.

“Why?” I asked, in surprise.

“Don’t you see?” answered one man “The Hatfields will never rest content until all the men who took part in this hanging have been killed. As the reader of that document, you will be reckoned as guilty as the rest! You ought to have known the clan code better than to have accepted that duty, which was none of your business anyway.” There upon I began to feel rather sorry I had consented to oblige.”

“Later in the day the camera-man brought me the picture I had engaged him to take…the photograph here reproduced. It was a print of the old celluloid type – long since obsolete in the photographic work. The fact that it was wet and had to be pressed between heavy blotting-paper, was a factor that afterwards saved my life. I had put several folds of paper around the picture and then stowed it carefully away in the inside breast pocket on the, left-hand side of my coat.”

“I noticed sundry scowling glances and over heard a few angry mutterings that did not make me feel any easier over the part I had involuntarily played in the execution. I took a walk around the deck before retiring. It was very dark and wet, and a few passengers were aboard. As the boat rounded a bend a figure passed me in a dark alley-way. I felt a sharp blow, and stagged to one side. The man passed on without a word; I thought he had been thrown against me by the movement of the boat. I reached my cabin and began to undress. I discovered a much more sinister meaning to the incident. The photograph, it will be observed, shows a ragged mark cutting through the figure of the preacher. This mark is due to the fact that a keen, thin-bladed knife had pierced my overcoat and jacket and penetrated right through the picture and the layers of paper surrounding it.”

Captured from the Wide World Magazine by Col. Garnet Clay Porter is this celluloid photo of the hanging of Ellison Mounts.

It is amazingly similar to the sketch of the photo printed in the Times in Philadelphia on February 26, 1893, and even more similar to the well-known photo shown below.

Note the small differences in these two pictures. Porter writes that Ellison is sitting in his picture. Note the men holding their hats and hanging their heads, in reluctance for some on the scaffold, as they seem to be engaging in conversation. Moments later a second picture was taken with Ellison shown kneeling, praying with Rev. Glover before he meets his maker. Porter is the man standing next to the preacher with the white envelope in his pocket holding the death warrant. Porter wrote that the death warrant was tossed and not returned to the sheriff after it was read aloud. Colonel Porter was an eccentric, a gambler, and had been arrested for hitting a jeweler in Kansas. He was really not even a Colonel, the title being a brand handed to him, he alleged, by a Kentucky Governor.

Porter next took a job in Canada, while keeping his Associated Press credentials. To his credit, Porter was mentioned in Who’s Who of Canada and given numerous accolades. Prime Minister Mackenzie King is quoted… “His memory will be cherished not only by former associates but by a host of friends throughout Canada.” He had been presented with numerous news awards for service to his craft. M.E. Nichols, Vice President and Publisher of the Vancouver Province, wrote “The title of greatness falls but rarely to the men who help to make newspapers, but he was in my considered judgment a great reporter.” [17]

Bringing to mind and quoting Frederick R. Barnard, “a picture is worth thousand words,” we now have two photos of the hanging of Ellison Hatfield-Mounts.

Col. Porter’s photo from the 1933 World Wide Magazine is indeed of the hanging of Ellison Mounts. Porter lived to be 79 years old and died March 6, 1945. [18][19][20]

Endnotes

[1] The Boston Globe, Feb. 20, 1890 (here a few sentences from the Boston Globe)

It was a great day in Pikeville….every arrangement had been made for the holiday. The hotels and boarding houses were filled with guests early yesterday afternoon and every inch of space utilized. The private homes were also invaded. Friends came from far and near, and relatives improved the occasion to make long deferred visits to almost forgotten kinsfolk. People came on foot, on horseback, mules, in wagons, by every imaginable conveyance. There were very few buggies in the country and no railroads, but a steamboat came up from Catlettsburg, 80 miles away, with a big load of excursionists from the towns along the river. The main method of transportation was on horse and mule.

The crowd was not an inviting one in appearance. These Kentucky mountaineers have passed all their lives for the main part in the direst poverty. Most of them were shabbily dressed in homespun. The men stuffed their trousers in their boot tops, and their home made and “store clothes” were alike of wonderful fit. There were a great many pockets about coats and trousers and most of these receptacles were suspiciously bulging with flasks of moonshine, packs of playing cards and deadly bowie knife or revolver.

To them it was simply a big holiday. Innumerable were the jokes and quips upon the terrible event so quickly approaching.

In one of the groups outside the jail, a mountain editor, Rev. S.D. Swimme, was soliciting subscribers for his paper, the Mountain Monitor. The editor is a great man in those regions, and he was followed by a crowd wherever he went, occasionally he received a subscription for his sheet. There were a number of Candidates on the ground also, and they were all actively at work.

[2] 1899 Johnson Hatfield trial transcripts.

[3] The Boston Globe. Feb. 20, 1890. Special Dispatch Louisville, Ky., McCoy’s Avenged. One of the Hatfield Gang Hanged. It was Pikeville’s Gala Day. Buxom Lasses Hug Their Lovers on Mule Back. Way Back Editor Increases Circulation. As the Drop Fell a Woman’s Shriek Came from the Mountains.

[4] The Boston Globe, Feb. 20, 1890.

[5] St. Louis Globe Democrat. Jan. 22, 1890. Special Dispatch to the globe Democrat, Louisville, Ky.

[6] The Big Sandy News Aug. 5, 1886. Rev. J.W. Glover is expected at the Camp Meeting next Sunday. He recently joined the Methodist Church.

The Big Sandy News, Apr. 6, 1894. There will be a debate on baptism at the new church house on Bear Creek, commencing April 24th, by Rev. J.W. Glover, Southern Methodist, and G.R. Justice, Baptist. The subject will be “Resolved, that immersion is the only true baptism.” Affirmative, Rev. Justice; Negative, Rev. Glover. Quite an interesting time is expected.

Greenup, Ky., Mar. 22. The Rev. John Wilkes Glover, of the M.E. Church South, dropped dead in the pulpit while conducting a protracted meeting at Farmington, W.Va. He was born and reared at Mt. Zion, this country, and was 65 years of age. He was a Union soldier; a widow and one son survive him. His burial took place at Mt. Zion Church under the auspices of the Odd Fellows and Masons.

[7] The Big Sandy News Aug. 5, 1886. Rev. J.W. Glover is expected at the Camp Meeting next Sunday. He recently joined the Methodist Church.

The Big Sandy News, Apr. 6, 1894. There will be a debate on baptism at the new church house on Bear Creek, commencing April 24th, by Rev. J.W. Glover, Southern Methodist, and G.R. Justice, Baptist. The subject will be “Resolved, that immersion is the only true baptism.” Affirmative, Rev. Justice; Negative, Rev. Glover. Quite an interesting time is expected.

The Big Sandy News, Jun. 20, 1913. Church Dedication. The new First Methodist Episcopal Church South of Pikeville, Kentucky, will be dedicated Sunday, June 22, by Rev. W.F. McMurry, of Louisville, Ky., Rev. W.B. Corder of Ashland, Ky., will have charge of the music for that occasion, and Mrs. Gertrude Wilhoit, of Louisville will preside at the organ. Rev. O.F. Williams, P.C., will be present for the dedication. The corner stone for this building was laid on the 24th day of last June, by the Masonic Fraternity on which occasion Bishop James H. McCoy, and Hon. Frank Hopkins made the principal addresses. The past year has been on of great concern on the part of the pastor and people, in the bringing this building, well equipped for all the work of the church in the congregation. This taken the place of the old church building which stood two squares below on Main Street. The erection of this building was begun in 1878, but was not completed until 1889 under the pastorate of Rev. J.W. Glover. This building was used for a court house, while the present church house was being erected. The Methodist Episcopal Church South was organized in Pikeville soon after the division of the Methodist Church in 1844. There have been many conversions at her alters and many have gone into the unseen world from its membership. All been years of her history have not been years of progress, but the faithful few have been brought to see a more prosperous day. There is now a very good membership, a good Sunday school, and a great field of opportunity for the Masters work. THE PASTOR.

The Big Sandy News, Mar. 27, 1903. Rev. J.W. Glover, a well-known physician, and for many years a traveling preacher in the Western Conference, M.E. Church South, died last week. Dr. Glover was stationed at Farmington, W.Va. He was buried at the family cemetery, near Frost, in Greenup County, the masonic Lodge of Ashland, of which he was a member, taking part in the service. He was well known in Eastern Kentucky.

Same paper as above – Greenup, Ky., Mar. 22. The Rev. John Wilkes Glover, of the M.E. Church South, dropped dead in the pulpit while conducting a protracted meeting at Farmington, W.Va. He was born and reared at Mt. Zion, this country, and was 65 years of age. He was a Union soldier; a widow and one son survive him. His burial took place at Mt. Zion church under the auspices of the Odd Fellows and Masons.

[8] The Courier Journal, Aug. 8, 1893. Hall Will Hang Friday. Gov. Brown refuses to interfere with the Judgement of the Court.

Frankfort, Aug 7., Gov. Brown has declined to commute the sentence of Henry Hall, of Pike County, for the murder of his brother, and he will be hanged at Pikeville, Pike County, next Friday. Hall’s friends interested themselves in his fate lately and secured the influence of some of the best people in that section in their effort for executive clemency, and a numerously signed petition was presented to the Governor. The Governor in declining to exercise clemency indorsed the following upon the petition: “The verdict of the jury imposed the death penalty and was fully warranted by the evidence. Hall cruelly murdered his brother. Many good citizens of Pike County ask that his punishment be commuted to life imprisonment, but the facts in the case do not justify executive clemency. I must decline to interfere with the judgment of the court.” Col. Wigginton (Weddington), of Pike County, who presented Halls petition to the Governor, says the condemned man comes from a profligate and ignorant family. His father taught his children to drink and gamble, and to engage in all sorts of debauchery, and he had not in all his life attended church as often as a half dozen times. He is perfectly depraved.

The Evening Bulletin Aug. 12, 1893. Public Hanging. Pikeville, Ky., Aug 12. Henry Hall was hanged here for the murder of his brother. The drop fell at 11:00. His neck was instantly broken. He made a confession on the scaffold and completely broke down. Fifty guards, armed with Winchesters, prevented any attempt at rescue. Ten thousand people witnessed the execution.

[9] The Interior Journal, the Kentucky Advocate and others

[10] Semi-Weekly Interior Journal

[11] The Boston Globe Feb. 20, 1890; In one of the groups outside the jail, a mountain editor, Rev. S.D. Swimme, was soliciting subscribers for his paper, the Mountain Monitor. The editor is a great man in those regions, and he was followed by a crowd wherever he went and occasionally he received a subscription for his sheet.

[12] The Public Ledger of Apr. 30, 1892 says; H.H. Salyards, a well-known newspaper man of Eastern Kentucky, leased The Pikeville Monitor. 12 Though, Swimme was still writing.

[13] Picture of Garnet Clay Porter from Winnipeg Tribune from Feb. 11, 1916.

[14] The Winnipeg Tribune, Feb. 11, 1916.

[15] Kansas City Times Jun. 1, 1888.

[16] This picture of Porter from the Vancouver Sun, 1923.

[17] The Province Mar. 7, 1945

[18] 1899 Omaha Daily Bee, Sat. Dec. 9, 1899.

[19] The Hatfield-McCoy feud and My Part In It. Col. Garnet Clay Porter. World Wide Magazine, Vol. 71, Published in Newnes, London 1933. (Cosmo Books in the UK).

[20] The Victorian Daily Sept. 19, 1945 – Winnipeg (CP) A memorial stone to perpetuate the memory of Col. Garnet Clay Porter, veteran editor, was unveiled here at Elmwood Cemetery Tuesday by M.E. Nichols, vice president and publisher of the Vancouver Province, in the presence of many former associates. Newspapermen and friends across Canada and the United States who knew him as “the Colonel” made the ceremony possible by their participation in the Porter Memorial Fund. Payingtribute to the Colonel, Mr. Nichols said: “The title of greatness falls but rarely to the men who help to make newspapers, but he was in my considered judgment a great reporter.”