Antebellum coal mining in Pike County was a hit-and-miss proposition, not only for entrepreneurs but for laborers, as well. Sometimes sufficient rainfall allowed the coal to be transported downriver, but dry spells just as often kept the coal boats moored to the riverbank. Even before the formation of Pike County on December 19, 1821, eight-man push boats were commonly used to bring supplies up the Big Sandy to the Upper Precinct District in Floyd County’s Peach Orchard Bottom, what we now call Pikeville. The push boats on rare occasion could even drift as far as the forks of the Russell and Levisa Rivers, providing there was a good spring or fall tide. The new dawn of steamboats started showing its presence as noted in Collins’ History of Kentucky “Annals of Kentucky” section. The first documented steamboat trip up the Big Sandy River was on May 20, 1837. The unnamed boat paddled upstream 90 miles to Prestonsburg, then meandered upriver an additional 25 miles to Pikeville. In 1843, a steamboat named Joseph F. Hatton, piloted by Allen Hatton, pushed all the way to Pikeville, causing quite an alarm among mothers and children, as well as livestock stationed near the landing behind the Public Square.

In order for steamboats to push up the Levisa River to current day Cattlettsburg, a massive amount of fuel was needed, a fuel other than wood. Coal, hotter burning and more economical, was introduced as the new fuel and the beginning of the energy revolution on the Levisa Fork of the Upper Big Sandy. The sudden need for coal propelled William Weddington and James S. Layne to form the first small commercial coal operations at the Pike and Floyd County line at the Mouth of Hurricane Creek. These notable landmarks were identified by an old surveyor known as Thomas Witten Botton, April 5, 1823, nearly a year and a half after Pike County was separated from Floyd County.

At the start of 1849, things on the Big Sandy River were starting to get more exciting with the everyday presence of faces never seen before. Mineral Speculators showed up, some from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York, looking for what the Indians called fire rock. With steam engines and iron rails for trains dotting the landscape, and mighty steamboats plying the Ohio and Big Sandy, the need for energy grew rapidly. By the year’s end, plans were made to mine coal and harvest timber for shipment down the Levisa fork of the Big Sandy River onto the Ohio River.

In order to ship coal or timber on any waterway in the State of Kentucky, you first had to get approval from the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Most of the Big Sandy River had already been approved for navigation from its water ways, but an Act was needed “to establish private passways to any point or points at which it may be desired to make a landing on any navigable stream in said county, to enable the applicant to take off timber or coal, under the same rules and regulations which govern County Courts in establishing private passways to courts, elections and warehouses.”

Chapter 63 was passed by an act of Kentucky Legislature and approved January 30, 1850. This Act applied to Pike and Floyd County; the same year Pikeville had gained its right to be an incorporated Town. According to Henry Scalf, there were mine entries at the Mouth of Hurricane Creek, probably near the Pike County & Floyd County line. James S. Layne & Son of Laynesville, (Lindsey Layne being the “son”) were each conducting a mine operation. Scalf listed the starting date as unknown, but it was most likely the Kentucky Legislators Chapter 63 approval of January 30, 1850, that would benefit the Laynes. Scalf’s research would show later entries for August 23, 1850. James S. Layne and his wife Adeline sold a 20-acre tract at the Mouth of Hurricane Creek to Sandy Valley Mining Company, composed of Casper Castner, Samuel Boggs, Fredrick Handman, and Charles W. Bunker. But even before the purchase of the mining operation from the Laynes, evidence of two companies could not be found in Kentucky Legislative Acts prior to 1850 conveyances. The exact mine location for this particular conveyance is not known, but consideration for $700 was a high monetary figure in 1850.

This purchase was not the first mineral deal involving the directors of Sandy Valley Mining Company. The names of the directors, Casper Castner, Samuel Boggs, William Hun and Fredrick Handman, started popping up in Land Survey entries on December 10th and 11th of 1849, almost 9 mouths before the Layne & Son purchase. These survey entries would be filed July 8, 1850. It’s uncertain how long the original founder of Laynesville had being producing coal, but it sure garnered the attention of the Sandy Valley directors. Another survey entry assigned by James Weddington was dated December 12, 1849, giving the directors full access to the property of James Weddington’s coal banks facing the Levisa River on the left side, at the mouth of Hurricane Creek. This survey and the 2nd future land assignment from William Weddington gave access to several thousand bushels of coal at the Mouth of Hurricane Creek.

With no records to rely on, it’s uncertain how many mining activities were conducted by Casper Castner, Samuel Boggs, William Hun and Fredrick Handman. By February 11, 1854, an Act approved by the Kentucky General Assembly, Chapter 185, was granted Big Sandy Coal and Mining. Large scale plans to establish the first commercial coal operation on the Pike and Floyd County line were soon under way.

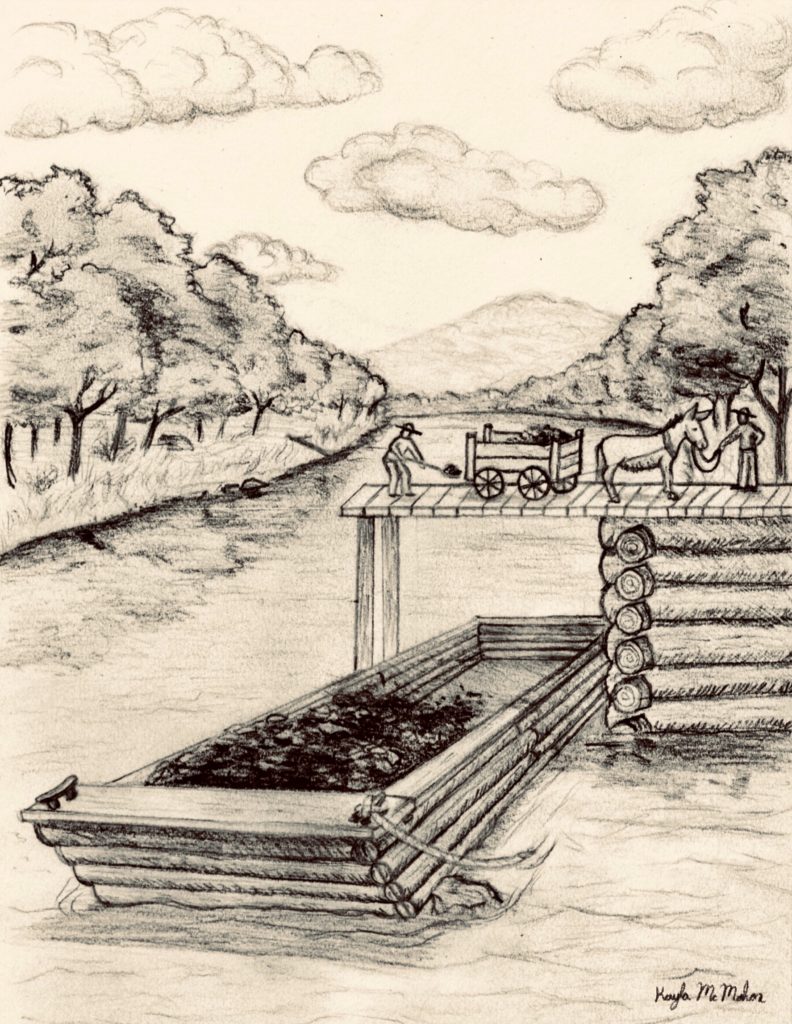

Ramps and wharfs built on the Levisa River by Big Sandy Coal & Mining Company, allowed the coal to be transported by carts from the mine portal, to be loaded directly onto push/ coal boats on the Levisa River. Coal could also be loaded directly on steamboats into its coal bins. As evidence that Big Sandy Coal and Mining was well under way mining coal, a number of lawsuits arose from the cost of camp construction and coal production. Court action from an 1855 case involved suppling coffee receipts owed by Big Sandy Coal and Mining Co. for coffee probably used by miners and managers. Suppliers of coffee were furnished by James Damron and Richard Damron.

Quite often simple human greed took the reins and lawsuits were in order. Below are several pages of a suit filed May 8, 1856, by Thomas Johnson, a “coal digger” of the time. Johnson claimed that Big Sandy Coal and Mining Company owed him for services he had performed. We have no way of knowing whether Johnson was entitled to the money he claimed, or if company management simply tried to gain by wearing down both his finances and his will to stay the course. The mine was located on Hurricane Creek near the line between Pike and Floyd counties. Johnson was ultimately paid a fraction of his claim.

Preparations had already been made for mining coal in anticipation of the spring tide that would carry it downriver, and for the steamboats that would be bringing merchant supplies up the Levisa to Pikeville.

The two invoices above show that Thomas Johnson, from February 9, 1856, until May 1,1856, loaded and hauled 196.5 cart loads of coal at the rate of 50 cents per cart. For every 10-foot entry in bank coal, he was paid $5.00.

The complaint gives us an idea of the primitive nature of mining in pre-Civil War Pike County. It is yet another page in the never-ending story of the conflict between labor and management.

On March 5, 1860, after 4 long years of financial short comings and lawsuits, Big Sandy Coal and Mining Company was still trying to gain dominance in the commercial coal market. Everyday new coal banks were showing up on the Upper Levisa River. Landowners with adequate seam height close to the Levisa River, stood ready to make their mark by supplying coal up and down the Ohio. Meanwhile, the board of directors were looking for a new financial arm to expand in readiness for the furious competition that had entered the coal market following David Dale Owens final report with the Kentucky Geological Survey. They found a past customer and buyer of one of Big Sandy Coal and Mining tracts of 700 acres in Floyd County, a sale that had taken place two years earlier in October 1858. The investor, a Cincinnatian by the name of James H. Laws, would fill that need. The directors would leverage 14 mineral tracts which they purchased in fee. The collateral pledged by Big Sandy Coal and Mining Co. gained them a sale of 150 bonds at $1000.00 each, enough reserve to fulfill their long-term plans. The bonds matured in 1880 at an annual interest rate of 7%. The standard rate of interest for 1860 was 6%. This information can be found in Pike County Clerks records, Book D, page 365.

The Industrial Census of 1860 listed 8 camp houses unoccupied at the Mouth of Hurricane Creek. Stephen Ferguson, occupation doctor, was the newest resident at Dwelling 902. William Weddington, listed as a farmer, occupied dwelling number 897, his home and 4275 acres of land worth $10,000.00.

In the journal of Col. John F. Stewart we’re told of a series of events leading up to the Wireman Shoals boat skirmish and gun battle around Bulls Gap, during the fall of 1862 at the mouth of Hurricane Creek. While having corn ground at the Hurricane mill, a number of Union soldiers took up quarters in the little coal camp houses that had been built for coal miners just years before. According to John F Stewart an effort was made to mine coal and market at this place. Recruiting officer Nathan A. Brown had his headquarters there at the mining camp. Location and source of the camp was noted in Stewart’s journal, but at the time of occupation by the Union Army there was no mining or work present. Mining most likely resumed at the mouth of Hurricane Creek after the Civil War.

It was also written by Henry Scalf that Laws would later take legal possession of the Big Sandy Coal and Mining Co. and their reserves, several years after bonds failed to pay off. The suit was finally settled July 7, 1900. Red exhibit shows the projected area of the mining operation in the late 1850’s.